Emmy nominated host of ABC’s late-night talk show Jimmy Kimmel Live! talks to the founding editors of Whitefish Review about fishing, family, and laughter in a changing world.

Interview by Brian Schott, Lyndsay Schott, Ryan Friel & Mike Powers

When my wife Lyndsay woke me up one night to tell me that Jimmy Kimmel had just subscribed to our journal, at first I thought she was joking. We had just been riding a fun wave of media attention for landing a post-retirement interview with David Letterman, and a number of new subscribers had signed up online. But Jimmy Kimmel, really?

The next day I did a little research and it started to make some sense. Kimmel was a big fan of Letterman. Jimmy loved to fly fish. He had just done a magazine photo shoot in Montana. I wonder, what would happen if I emailed him?

Many months later, I sat with my wife and two best friends around a table in the Whitefish Review office on November 16, 2016. We smiled at each other as the happy voice of late night comedy came over our speaker phone.

Jimmy was kind, funny, thoughtful, and generous. I continue to be impressed and inspired by people like Jimmy, whose time is at such a high premium—and they still keep an eye out for the little fish like us. —Brian Schott

Jimmy Kimmel: Hello?

Brian Schott: Jimmy!

JK: Brian?

BS: Hello.

JK: What’s happening? How are ya?

BS: I am doing well. How are things with you?

JK: Everything’s good thank you. Just chugging away here as we get near the end of the year. Getting things all wrapped up.

BS: Well, good. Thanks so much for taking the time to chat with us today.

JK: My pleasure.

BS: So I’m sitting here with my wife, Lyndsay Schott, who is one of the founding editors and the brains behind the operation, as you can imagine.

JK: Hi, Lyndsay.

Lyndsay Schott: Hi, Jimmy.

BS: And I’m here with Mike Powers, another founding editor, and Ryan Friel, our other founding editor and resident fishing expert.

JK: I’m feeling… I feel like I might be in trouble now that there’s a round table assembled. [laughter]

Ryan Friel: No, it’s more of a square here Jimmy. And the word “expert” of course is used very loosely, as you know in the fishing world.

JK: All right. Yeah, for sure. [laughs] So what do you want to talk about?

BS: Well, first, we were really sorry that your bid for Vice

President of the United States fell flat and we were obviously really surprised about it. It looked like you had the polling numbers. What happened?

JK: I’m not sure what happened. My mother told me that she got a note from a friend who lives in DeKalb, Georgia who said it was reported in the local newspaper that my name was written on ballots there. So that seems to have been my stronghold. In that area, I got at least one person, according to the newspaper, who wrote my name in. Turns out, it’s best to have a running mate if you want to be the running mate.

RF: Right…

JK: In retrospect, maybe I shouldn’t have gone it alone. But, you know, the next campaign will probably start in about three months. So… I’ll get going on that.

BS: So are you thinking you’ll stick with the VP role again or do you have higher sights?

JK: I might lower my sights. I might run for like, Secretary of the Interior.

BS: Well, good. We could use you.

JK: Run for a cabinet position. [laughter]

BS: So we can’t ignore talking about the election just for a minute.

It’s obviously a strange time in American politics. Last night on your show you said you wake up thinking about it. It’s obviously deeply troubling to a large portion of the population and we just wanted to grab a few more thoughts from you about Trump winning the election.

JK: Well, it just goes to show you, nobody knows anything, do they? I mean it’s a lot like fishing in a way. It should be a good day, the conditions are perfect, guys have been catching a lot of big fish—and then you come home with nothing. [laughs] And you know it’s funny that people call it an upset because, in a way, there’s no such thing as an upset. I mean, I suppose if The Rock [Dwayne Johnson] was fighting Danny DeVito and Danny DeVito won the fight—that would be an upset.

But I think it is interesting to see everybody saying, “Now is the time to come together.” I don’t recall that happening when Obama won and a lot of people were upset. And hopefully we will do that. And hopefully we will be pleasantly surprised by our new president. I don’t know if that will happen, but I’m sure we will be surprised by our new president.

RF: Well said.

LS: Well, I’m the girl in the fishing boat. You know, I’m trying to break up the locker room talk today. [laughter] And I love the movie, “Back to the Future.” So you know, a lot of women and minorities—we can’t overlook that they are feeling a little unheard in our country at this time. Do you think that I have to be afraid, or is there any risk that we are moving back in time? Do I have to worry about, you know—the flux capacitor at this time?

JK: [Laughing] I don’t know if I’m qualified to answer that question. The problem is, I think, that a lot of people didn’t vote. I think if you’re going to point to anything, it’s got to be that. I saw a story on the news last night, about a bunch of protestors in Oregon, and the local news decided to check their arrest records next to their voting records. And it turned out that something like sixty of them hadn’t registered to vote or voted. And, that’s just… you sometimes wonder if people shouldn’t be forced to vote. But then, should we be giving a vote to someone that doesn’t want to cast one in the first place? You know, if anyone’s not feeling heard, they should look at the people who decided not to vote this time around. I mean, whatever reason you have for not voting, my guess is that it’s a bad one. LS: It’s hard to protest something that you didn’t participate in.

JK: Well, not with those people I guess. I think sometimes people don’t put those two things together…but they definitely should. And hopefully four years from now, which is always a long time away, people will remember, umm… this.

Mike Powers: Hey Jimmy, this is Mike.

JK: Hey, Mike.

MP: We all know laughter is powerful, and let’s talk about it. Can we use laughter to bring about change in this country?

JK: Last year, as in, what, 2015?

MP: Oh, sorry, I mean, laughter.

JK: Oh, laughter. I’m sorry. [all laughing] Yeah, I think you can. I think that a lot of young people especially—their opinions are shaped by the opinions of the comedians they listen to, and the people they look up to. I do think, especially when people’s opinions are being formed, humor makes a big difference.

Unfortunately, I think a lot of it is preaching to the choir. We made a video [on Jimmy Kimmel Live!] about climate change, where I thought, “What can you say to people that will make them actually consider your point of view rather than just being combative or insulting?” I decided that the angle we would take was climate scientists. The vast majority of them have nothing to gain, financially, from opposing climate change and working to slow it. I always wondered what the motivation is for these people who don’t believe that climate change is man-made. Why would scientists warn us about something that isn’t real? There’s no benefit to them.

So we made a video, whose message was basically, like, “We’re not fucking with you. Why would we fuck with you? We went to eight years of college. Do you think this is why we did it? So we could trick you into thinking that climate change is happening?” And it was a pretty effective video—a lot of people saw it. And for me, that’s what I like to go for. If you really want to change a person’s opinion, insulting them is not the way to do it. It’s to be clever, and make them stop, and actually consider it. Now with that said, I don’t know that we changed anyone’s minds, but we definitely didn’t hurt the case.

RF: Hey Jimmy, Friel here. With that said, are there any effects that you have seen in your time fishing, or that you could envision is going to happen with our cold water fisheries in the upcoming years?

JK: Well, I’m part of a group called American Rivers. I don’t know if you’ve heard of it?

RF: I am familiar.

JK: Well, they’re trying to get rid of those damn dams, in as many places as we possibly can. I think for me, fishermen are among people who understand what’s going on, in a real way, how our land and resources are affected by these energy companies whose goal is to make money. And that’s fine, but when it comes at the expense of everyone, it’s not fine. I think that fly fishermen in general tend to be a more thoughtful group. And I think that people should listen to them. Almost all of the people involved in American Rivers are fly fishermen. And of course, there’s the selfish aspect to it. You want to have the best fishing you possibly can. But I think great fishing equals a healthy environment. Those things go hand in hand.

So the more we can do to make the fishing better, the more we can do to make the country better, and the world better. Here in Los Angeles, there’s a group called “Raise the River”—they’re trying to get the LA River flowing again. Right now, it’s a cement water channel in most parts. It used to be a real river, and there were fish in it, and steelhead. To me, it would be a beautiful thing if they were able to get that river flowing regularly again.

RF: I think that you’re right, that most anglers, maybe fly fishers in particular, see that cycle of life in the ecosystem, and they want to be back in the water. And if we take that away from them, well, they can’t go stand in the water and wave a stick anymore.

JK: Yeah, it’s hard for people who aren’t fly fishermen to even understand the idea of catch and release. That’s what most people ask me about. They are puzzled by this. They are like, “Why would you even bother to fish if you are releasing the fish?” It’s almost impossible to explain, other than to tell them, “If we didn’t release the fish, there wouldn’t be any in ten years.” And even then, they’re still scratching their heads. I think you really have to be there to get it. I know I did.

For years I grew up bait fishing. On the off chance we caught something, we gutted it and ate it almost immediately. And we were very excited. And the idea of releasing these fish was an alien one to me. But now, I can’t even imagine intentionally killing one of these fish.

RF: Right. My brother and I grew up that same way. You know, you would just bonk every fish you caught and eat it.

JK: Yeah.

RF: And now, my smart-ass comment to people, as I’m trying to explain to them what we are trying to do is, “Well, you can only eat them one time. That’s it.”

JK: That’s right.

RF: I saw that you did some winter fishing on the Gallatin River. I assumed it was a nymph game over there, just by the temperatures.

JK: That was really a photo shoot more than we were fishing. Typically I much prefer dry fly fishing. But it was very cold, so we were nymph fishing. But that was primarily for a magazine photo shoot. They asked me to do a photoshoot and I really didn’t want to do it. And they said it was a “bucket list” issue. I think they just wanted me to pose on the cover with a bucket or something dumb. [laughter]

And I said, well, if you’re really looking for a bucket list item, I’d love to fish that river. You know, I saw the movie, A River Runs Through It, and that idea has always excited me. And they said they would set it up. And they did, so I couldn’t say no.

RF: Right, of course not. And you did a Smith River float this summer, didn’t you?

JK: You know, my Smith float got canceled due to weather conditions. So instead we just rented a house and we fished on the Beaver Head and the Big Hole.

RF: Good spots there too. I just got back from the Missouri River.

JK: Oh, you did. Yeah, we had a lot of fun. But I was really, really excited about that float trip. One of these days I’ll do it.

RF: It’s fantastic. And it sounds like you know. Weather considerations can be the issue. You can hit it spot-on and have great dry fly fishing or you can wake up in the snow and brown water.

JK: They were saying we wouldn’t have even been able to get the boats through, so it would have been a lot of dragging the boats through gravel.

BS: So let’s circle back to David Letterman for a few minutes, which is really how we got here with you today, Jimmy.

JK: Oh, yeah, that’s right.

BS: So Lyndsay told me one night, “Hey, I think Jimmy Kimmel just subscribed to Whitefish Review.” And we were like, “wow.” [laughter] Go figure.

LS: He didn’t believe me was actually, I think, the first response.

[more laughter]

JK: Well, it’s interesting. I know Dave’s very discriminating, so I figured if he decided to be a part of it, it had to be good. And so I subscribed. And you know, when I’m out fishing, typically the word “whitefish” is not a good thing.

RF: Yeah… right?! [laughter]

JK: But you guys do a nice job with it and I was impressed with the publication overall—not just the Letterman story.

BS: Thank you.

RF: Thanks, Jimmy. As the fisherman in the group, you can imagine how I struggled, even more than these guys, with the title.

JK: Oh, you did. Exactly. It’s funny. It becomes a little bit tongue and cheek if you like fishing.

BS: Don’t you have to kiss a whitefish when you haul one in?

RF: You do it one time, maybe.

JK: Yeah, right. I don’t kiss anything with a moustache.

[laughter]

BS: Let’s talk about David Letterman for just a minute because we know he was a big influence on you. Can you speak about that influence?

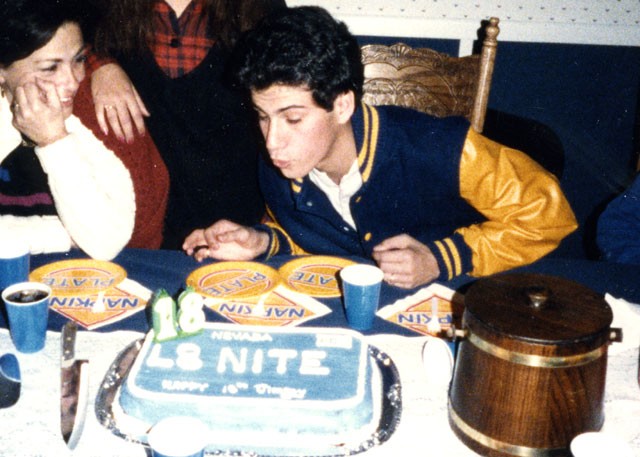

JK: When I was a kid, there were kids who were known— like he’s the kid who sells pot, he’s the quarterback on the football team. I was the kid who watched David Letterman. It was really what I was primarily known for and there weren’t a lot of kids who watched David Letterman. It increased over the couple of years I was watching in high school, but I’d write Late Night with David Letterman on all my book covers. My license plate on my car said L8NITE. I’d have viewing parties at my house when he had a special on Friday nights. I was completely obsessed with the show.

And most people mistakenly think that this is what made me dream of one day doing a late night talk show. It’s really not true. That was… I don’t know whether you’d call it an accident or a coincidence or just something that happened. But really, what I was interested in was watching a late night talk show. I never really thought about hosting one. It never occurred to me that there would be a show other than Johnny Carson and David Letterman. Or that either one of them would ever go off the air. It just never entered my mind. I know that’s dumb, but it’s true.

MP: Congratulations on having the longest running late night talk show in ABC’s history.

JK: Thank you. It was a low bar to clear.

MP: At least you got over it. As you look to the next decade. Are there any specific things you want to accomplish whether it’s personal or professional?

JK: Well, the job’s a little bit of a grind. So, the challenge for me is continuing to do new things and to not get stuck in a rut—to keep myself interested. I think that’s the biggest challenge, because you’re doing basically the same thing every day. And you don’t ever want it to feel like it’s a regular job. I think that when you start feeling that way is when you should probably stop doing it. So for me, it’s a challenge to not be just funny, but creative every day and to be able to continually improve the show. I like it when I look back at a show from three years ago and think, “Oh, that was no good,”—because it indicates we’re getting better at it. So as long as we keep getting better at it, I enjoy doing it. But when we don’t, I’ll really have to stop and evaluate what I am doing with my life because there are other things I’d like to do.

BS: When you think back to Letterman’s career and observe him in retirement—and some of the thoughts he’s had about his career—has it caused you to shift any approach to your show?

JK: No, I don’t think so. I think if anything, I try to remind myself to enjoy what I’m doing while I’m doing it. While I’m doing it, I do have a tendency to look ahead. I do fantasize about buying a house in Idaho, Montana, or Wyoming and spending a lot of time fishing—and not working. But I also know myself well enough to know that I will miss these days. So I do want to try to be present and try to be in the moment and try to appreciate the time as it passes. But, I usually fail at that. [laughter]

LS: So, a little bit of time has passed for you this week, huh? You just had your birthday the other day. Happy 50th!

BS, RF, MP: 49th…!

JK: 49th, 49th.

LS: Oh, I mean 49th. That was a joke.

JK: Oh. Ha, ha. You’d be surprised at how many people I work with got confused about that.

LS: What does it feel like to be staring at 50? We’re very young here, you know…

RF: That’s also a lie.

LS: Yeah, we’re lying.

JK: Well, it’s upsetting. You know, I won’t lie. It’s upsetting. I find myself trying to figure out how old my dad was when we moved to Las Vegas. And how old my dad was when we moved to Arizona. And then compare myself to that, just to put it in perspective. The funny thing is, and I guess the good thing is, the older you get, the younger everyone seems. So, now all of a sudden, you hear somebody dies—and they are 73 year old—and you say, “Oh my god, they were so young.” Whereas when I was 25, somebody was 73 years old and they died and I said, “Well, they lived a long life. Thank god.” It’s really all about your perspective. The older you are, the younger everyone else is. Including people older than you.

RF: True tale.

BS: So you have a young daughter.

JK: Yeah, she’s almost two and a half.

BS: You seem to get a kick out of how kids think and the things that they say. Do you have any funny lessons your young daughter has taught you recently?

JK: Well, she’s taught me that my belief that I was in charge of the house—that I was mistaken. We are really her servants. We are there to do her bidding. There’s no two ways about it. She wakes up in the morning and tells me what kind of pancakes she wants and then just directs us throughout the rest of the day and all weekend long. And, I love it. I really get a kick of out of watching her learn to speak—that is a lot of fun for me. She’s really funny. The things she picks up on are always surprising. I have two older kids, a 25-year-old daughter and a 23-year-old son, but I forgot about all the fun stuff that goes along with it. I have to rush home every night just to make sure I get an hour in with her before she goes to sleep.

LS: Have you ever taken her candy away? Like your bit on the show?

JK: I did try it, but she didn’t really bite. She got focused instead—there was some dirt in the bucket—she has the attention span of a two year old because—because she is two, you know. I’ll try it again next year and see what happens.

MP: We’ve noticed that family is important to you and that you incorporate some of your family into the show. Does this help to keep you grounded in Hollywood, Jimmy?

JK: Well, I think it does. But I don’t think that’s why I did it. I mean, all the people in my family who work for me are very qualified and do a great job. That is always the first thing. I wouldn’t hire somebody just because they needed money. People have to carry their weight. It’s not fair to the rest of the staff if they don’t. For me, part of it is, I’m at work so much. It’s just a way to keep in touch with everybody. Since I don’t have any real off time, I found that bringing them into the workplace was good. My wife works here, my brother, my cousins Sal and Mickey. My son is a production assistant here, and there are a few other relatives scattered throughout.

MP: Yeah, it’s pretty cool.

BS: Any must read books that you’ve come across lately?

JK: You know, there is one book that I think is an interesting book for people to read. I don’t know how many people would actually read it, but it’s a book about the history of the tomato. I think it’s called Ripe. I’ll look it up while we are talking. It’s a book about the tomato, not just how it came to be popular in the United States and in North America, but also how it’s shipped to you, how it’s grown, all the terrible things we’ve done to turn the tomatoes we get in the supermarket into red rubber balls. Yes, it’s called Ripe: the Search for the Perfect Tomato. [by Arthur Allen] You know if you are looking to read about 300 pages about tomatoes, I couldn’t recommend a book more than this one. [laughter]

BS: Any authors in your life that influenced you?

JK: I love Kurt Vonnegut. You know if I were forced to pick a favorite writer, it would probably be him. When I was a kid I always loved reading Hemingway—that’s part of what got me interested in fishing and being an outdoorsman, which was not part of my upbringing. We grew up in Brooklyn and Las Vegas—and I think you could describe us as “indoorsmen”—for sure, that was our family. Tom McGuane is another writer I like who I got an opportunity to fish with on a bone fishing trip. He’s a great guy.

BS: Yes, Tom’s been a great supporter of the Review as well. We got to watch that episode Buccaneers & Bones where you fished with McGuane and Tom Brokaw. It looked like a hoot.

JK: Yes, Buccaneers and Bones. That was a mess. Oh… It’s hard enough, my first bone fishing trip. And you know, it’s windy and everything. And, I’ve got camera boats circling and scaring the fish off every single time.

RF: Of course.

JK: I was like, “Oh please, will you guys go away and let us fish.”

RF: Let us just get a couple and then come back.

JK: The good thing is, the first bonefish I ever caught was professionally filmed. So that is a nice memento. The bad part was watching me flail helplessly into the wind.

RF: That’s all of us though, that’s all of us.

JK: Trying to remember how to double-haul in not so great conditions.

RF: Yeah, there’s no one who’s good at it. I don’t care what they say. [laughter]

BS: Well, we certainly would like to invite you to come and fish with us in Montana sometime.

JK: Send me an email and when I figure out my vacation schedule, maybe I’ll take you up on that. We like to try new spots and we’ve not been up there.

RF: Yeah, we would love to have you up here for sure, Jimmy.

JK: All right, thanks guys, appreciate it. Nice talking to you and keep up the good work.

MP: And Jimmy, thank you so much for speaking with us today. Our apologies to Matt Damon, but we ran out of time.

JK: [laughs] I’ll pass them along.

Illumination from the Mountains of Montana

If you enjoyed this, please support this independent literary journal.

Help sustain the Whitefish Review as a monthly donor, annual donor, or one-time donor. Whitefish Review is a 501(c)(3) non-profit so your gift is 100 % tax-deductible.

Subscribe to the print journal, order a single copy, or buy a T-shirt.

You can also find us on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter.

Thank you for supporting the arts!